THE ART OF THE QUILT

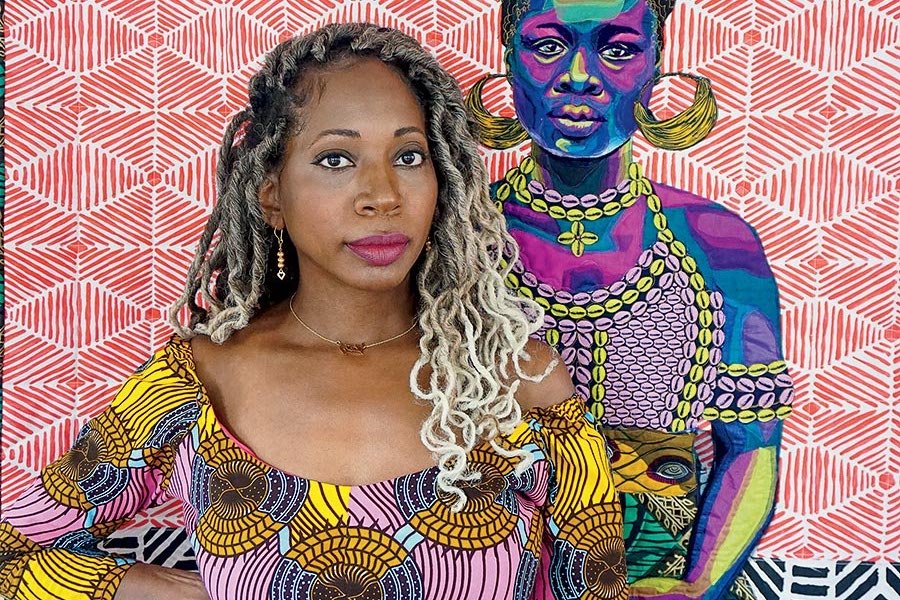

Bisa Butler

Award-winning, New Jersey-based artist Bisa Butler creates exquisite, vibrant and stunningly powerful textile art that celebrates African American life. Inspired by photographs, her reinvention of quilting as an art form uplifts those who have been marginalized or misrepresented.

Butler’s intricate portrait quilts are truly founded on love. A love of youth, family, community, and Black history. She brings to life the famous and the anonymous by translating black and white photographs into dazzling, colorful appliqued art pieces. Her quilt creations have created a surge of interest in quilting and her works now count among the permanent collections at Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, the Art Institute of Chicago, and about a dozen other art museums nationwide.

Bisa Butler in front of Dahomey Amazon (2002) © Bisa Butler.

Her approach to her art is informed by her training as a painter and her childhood experiences of sewing with her mother and grandmother. Through it she reveals essential – often hidden -- truths about beauty, strength, and fragility in the human experience.

The Love Quilt Project caught up with the artist, quilter and former high school teacher to learn how she aims to use her beautiful and evocative art to engage, create a narrative and speak to those who view it.

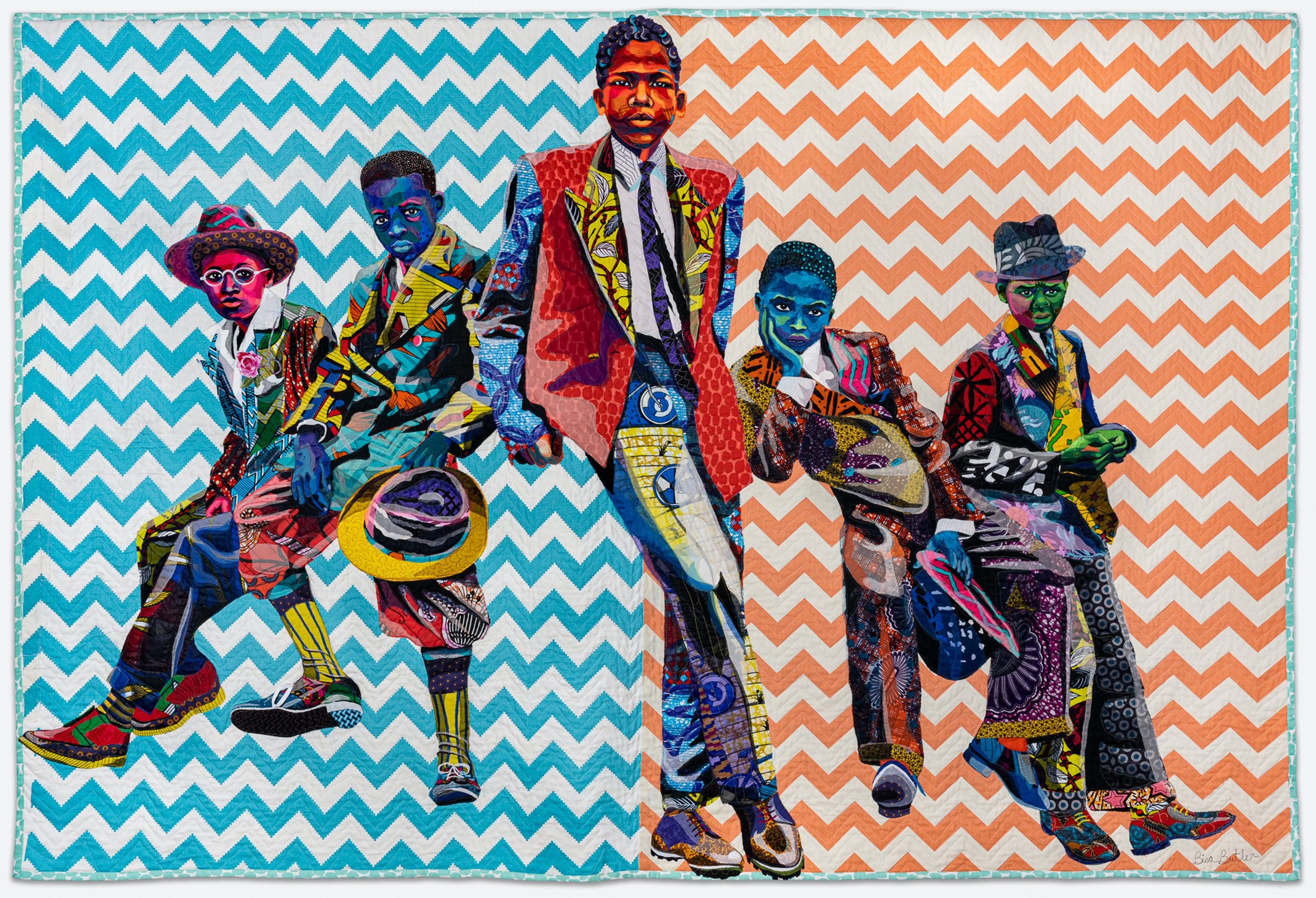

The Safety Patrol (2018). Cavigga Family Trust Foundation. © Bisa Butler. This piece took a staggering 400 hours to make.

How did your passion for art and quilting begin? “I feel driven to tell my side of the story – that African Americans have a lot to be proud of, that we take care of and love our children, that we believe in family, we value education, we work hard, and we belong here. Every human being is equal and I hope people see that when they view my work. A billionaire has no more or no less value than someone who sweeps floors. We are all in this together and until we know both sides of the story, our history will be incomplete.”

What inspired you to start creating your quilting art? “It is at Howard [University] that I was taught by the AfriCOBRA – The African Commune of Bad and Relevant Artists – founders like Jeff Donaldson, who was my Dean of Fine Arts, and Frank Smith and Wadsworth Jarell, who were professors. We were taught to be proud of our African heritage and always present our people in a positive light. They taught us that we had a responsibility to document and correct the misinformation that had been told about our people, and about Africa. We were to use our art as a tool to tell our side of the story to the masses and the mainstream.”

Detail from Warmth of Other Sons (2020). The Newark Museum of Art. © Bisa Butler

You chose such vibrant fabrics. What role does color play in your work? “I love color, I grew up in the ‘70s, so I want all of it all the time! I’ve always had a personal attraction towards bold colors and textures. I find it amazing – the ability to depict very specific characters – and you can tell this is a Black person, although the person may be [portrayed in fabric as] blue or yellow. That is why I like to use black and white pictures, there’s a sense of endless possibilities of color.”

Tell us about the Warmth of Other Sons which is displayed at the Newark Museum. “It is dedicated to the African American people who came from the South up to the North during the Great Migration. The name of the piece, The Warmth of Other Sons, is actually taken from the phenomenal book by Isabel Wilkerson called The Warmth of Other Suns about the African American migration. That's what sort of inspired me to create this piece, along with knowing the stories of my own family. The only difference in the titles--the book is "suns," s-u-n-s, as in people are searching for the warmth of other suns, other places, prosperity. I changed mine to s-o-n-s, as in the warmth of other sons, as in the warmth of other people, the love and the affection, the blood and humanity of other people as a Black people.”

Detail from The Mighty Gents (2018). Beth Rudin DeWoody. © Bisa Butler

How do you evoke such emotion in your quilts? “By presenting all of my figures with a richness and dignity they deserve, whether they are from a humble background or the upper classes. I hope people view my work and feel the value and equality of all people. All of my pieces are done in life scale to invite the viewer to engage in a dialogue – the figures all look the viewers directly in their eyes. I am inviting a reimagining and a contemporary dialogue about age-old issues that are still problematic in our culture through the comforting embracing medium of the quilt. I am expressing what I believe: the equal value of all humans.”

There are an incredible number of different types of fabric in each work. Where do you find all these? Do they have any certain significance to you? One of the best things about working on a wider national scale is that more people see what I’m doing, so I’m getting help finding fabrics. Before, all I had were my mother’s and my grandmother’s leftover fabrics because I couldn’t afford to buy new fabrics, and they had so many remnants that I didn’t need big pieces. I started out using mostly dressmaker’s fabrics. Traditional quilters would never be using silk and lace and chiffon all together, but those were what was available. My mother had bits of fabric from wool to gaberdine to tweeds and my mindset was, “What can I do with this?”

Southside Sunday Morning (2018). Private Collection. ©Bisa Butler

“But that forced me to expand my definition of what a quilt could look like. My grandmother used a lot of vintage African fabrics. African fabrics only have a short run—companies will put them out for a month and then they retire that print and that’s it. One print had these squares on it and for whatever reason women in the marketplace saw it and they called it “billionaire.” It got really popular and so it became like a status symbol. If you were wearing that billionaire fabric, it meant that you bought it within a certain month. It is very cool because when people see it they say, “Oh, I know that fabric. I remember when billionaire came out.”

You were a high school art teacher for many years. Do you think that teaching had any effect on your work? “Oh, for sure. The influence of the kids helped a lot, being around their energy and their interests. I started doing these images of children, especially when I was getting ready to leave teaching and was feeling sad about it. I made some of my favorite pieces then, like The Safety Patrol and South Side, Sunday Morning. I had a student, this young girl Vivi, and her mom owns a yarn shop in town. She just came in with a big bag of fabric and was like, “Oh, I was just thinking about you, Ms. B.!”